Getting to Know My Trauma: A Humble Treatise on PTSD

“Healing Brain Fog”, gouache on paper, 16” x 12”, 2022.

Sometimes, I suffer from creative blocks (painter’s and writer’s), and this has been one of those times— hence the tardiness of my newsletter. When I was a painting professor, I assured my blocked and distressed students that this was perfectly normal. I gave them suggestions: switch mediums! Paint with your non-dominant hand! Start a new series of paintings that can be accomplished daily. Paint from nature....paint from poems...go for a run...get out of town. There are so many ways to jolt one’s creative mind to release the passion and vision it harbors!

I've decided my block is the result of a big flare up of my chronic illness symptoms. The pain is distracting, and the brain fog exacerbates my mind, and makes thinking draining. What's causing this recent flare is mystifyingly complex, but is partly due to a disorder that I didn’t know I had. And so, since lately I’ve been living a life of inflammation and pain, I thought I would write about why that might be. This is more of a geeking-out on neuroscience treatise, rather than an essay on creativity, so bear with me!

Take a moment to consider what you know about PTSD, or Post-traumatic stress disorder. Most people use this term in everyday conversation as a way of indicating their strong emotions: “I have PTSD about exams,” “that girl/guy triggers my PTSD.” But they’re talking about emotions, not a medical diagnosis. Intense emotions are normal: we feel them, and most of the time, we recover quickly from them, returning to our baseline. I thought I understood PTSD until a few months ago, when I received my own PTSD diagnosis from a medical professional—my therapist. Actually, my diagnosis is complex PTSD, which unsurprisingly, makes it more complicated to treat and to heal.

If you’re anything like me, think PTSD and what comes to mind is the classic stereotype: a Vietnam veteran, who suffers from nightmares and flashbacks from his war experiences that cause him to believe he is reexperiencing those traumatic events. When triggered by, let’s say, fireworks, his nervous system thinks he is back at war. He may drop to the ground involuntarily. In life, he can’t control his emotional outbursts, which means he can’t maintain relationships, he can’t keep a job, and he probably has insomnia. Sadly, this stereotype is the lived experience of many war veterans. It is that debilitating, it does ruin lives, and it’s an invisible illness of the mind, just as real as diabetes or cancer.

What’s misleading about this stereotype is that although on average, veterans suffer more PTSD than civilians, more women suffer from PTSD than men. About 8 of every 100 women (or 8%) and 4 of every 100 men (or 4%) will have PTSD at some point in their life. This is in part due to the types of traumatic events that women are more likely to experience—such as sexual assault—compared to men.

These are the women in your everyday experience: the female coworker you may work beside, the woman who teaches your yoga class, the barista who hands you your coffee with a smile, the social worker who treats patients with trauma-history (whose research is me-search). Worldwide, approximately 1 in 3 women have experienced physical and/or sexual violence, often by an intimate partner. Here are some more staggering statistics about global sexual violence from the National Sexual Violence Resource Center:

· In the US, one in five women and one in 71 men will be raped at some point in their lives

· 91% of the victims of rape and sexual assault are female, and 9% are male

· One in four girls and one in six boys will be sexually abused before they turn 18 years old

· 81% of women and 35% of men report significant short-term or long-term impacts such as PTSD.

So though not every person who has been sexually abused has PTSD, many do. PTSD can be cause by any traumatic experience (not just war, or sexual violence) and is a leading determinant for social security disability.

PTSD is generally caused by a single traumatic event, and complex PTSD is generally caused by repeated traumatic events. In The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma, one of the most important books on the effects of trauma on the body, Bessel van der Kolk writes: “Trauma is not what happens to you, but what happens inside you as a result of what happens to you.” In other words, trauma is subjective. Two people could experience the same event, and only one might be impacted in a way that leads to PTSD.

Have you heard of the ACEs, in the context of trauma? ACEs stands for Adverse Childhood Experience(s), or potentially traumatic events experienced in childhood under the age of 18. You can take an ACEs questionnaire yourself, but to summarize, an ACE is: experiencing (or witnessing) violence, abuse or neglect; having a family member attempt or die by suicide; sexual abuse; growing up in a household where a family member has depression, substance use problems, instability due to parental separation and /or having a parent in jail. This is not a complete list, but it gives you an idea.

Why ACEs are important is because they impact all aspects of a child’s future health, both mental and physical. According to the CDC, adults with even one or two ACEs are at increased risk for chronic diseases and leading causes of death, such as cancer, diabetes, heart disease, and suicide. Extended or prolonged stress from ACEs can negatively affect children’s brain development, immune system, and stress-response systems. These changes can affect children’s attention, decision-making, and learning. According to the CDC, “children growing up with toxic stress may have difficulty forming healthy and stable relationships. They may also have unstable work histories as adults and struggle with finances, job stability, and depression throughout life. These effects can also be passed on to their own children.” And people with six or more ACEs die nearly 20 years earlier on average than those without ACEs.

Having ACEs does not guarantee one has PTSD, because it’s the way one’s nervous system handles and processes trauma that leads to PTSD. But ACEs put a child at a much higher risk of developing PTSD.

In my long journey with chronic illness, I’ve learned not to identify too much with my diagnoses. Doing so can lead to a victim mentality, and a kind of rumination and powerlessness which inhibits the healing process. But learning about complex PTSD has helped me understand some of my triggers and symptoms, and why I might be having a hard time healing. Without going into detail, I have 3 ACEs, none of which I ever discussed with anyone until I was in my 40’s in therapy. Coming to terms with my ACEs has been pivotal for me, but healing these deep wounds and entrenched behavioral patterns is the hardest thing I have ever tried to do. I’m still a work in progress, and I still have a long way to go.

People that know me know that I live on a constant roller coaster of chronic illness, experiencing long, unpredictable flares and shorter reprieves from those flares during the year. My trigger is not just mold toxins, or tick-borne diseases… I am also triggered by my own PTSD. And as I learn about my body through somatic experiencing therapy, I’m becoming aware of how easily— and often— I have a PTSD response to an event that may not be physically threatening, but feels very emotionally threatening. These triggers can cause physical symptoms in my body.

Ok, so how the heck does this happen, how could PTSD cause physical symptoms? Enter the fascinating field of study called psychoneuroimmunology, which explores the complex interactions between the nervous system, the immune system, and the psychological processes of an organism. Psychoneuroimmunology explains clearly how PTSD could manifest as body-wide physical pain and systemic inflammation in my body. There are many resources, but one I really like is an interview with Dr. George Slavich, the director of the UCLA Stress Lab who studies the effects of stress on the immune system.

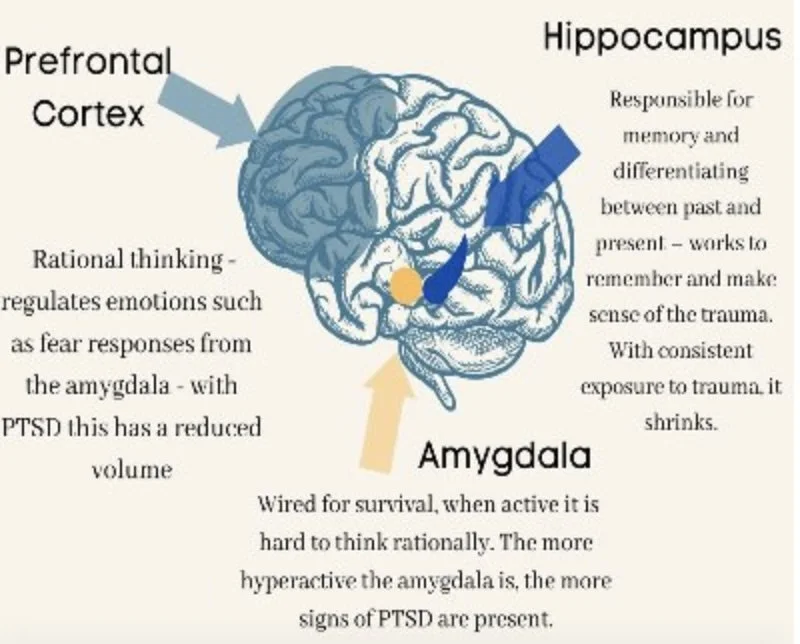

In it, he describes how trauma affects a child’s developing brain, causing the brain structure called the amygdala to become enlarged and hyperactive. The amygdala is a key structure within the limbic system, a brain region primarily responsible for processing emotions, particularly fear and threat detection. Trauma can also cause the pre-frontal cortex, which is the rational thinking center, to be underdeveloped and underactive. Slavich says there was a recent discovery of an anatomical part of the brain not previously known, which runs alongside the brainstem, called meningeal vessels, which he calls the cytokine superhighway. This superhighway is a direct connection for inflammatory cells (cytokines) in the brain to access the periphery of the body. In other words, inflammation travels from the brain into the body easily.

So how does stress lead to inflammation, and how can the immune system change moment to moment depending on how you’re feeling emotionally? His lab has shown that five minutes of social stress can change an immune system from a non-inflammatory state to an inflammatory state. The key thing about stress is your appraisal of environment. Stress is your perception of the environment, so if your brain detects a threat (you think you are under threat) it can cause changes in the sympathetic nervous system, which then causes changes in your immune cells.

You may know there are two aspects of your autonomic nervous system: the sympathetic nervous system—or fight or flight—and your parasympathetic nervous system—or rest and digest. The parasympathetic NS is governed by the vagus nerve, descending through the neck, chest, and abdomen, branching out to various organs. As a rule, you can only be under the regulation of the sympathetic NS or the parasympathetic NS at one time, but not both. If your sympathetic NS is activated by a perceived threat, your brain causes the release of various stress hormones/neurotransmitters (epinephrine, norepinephrine, and cortisol) to which your immune cells have receptors. Your immune cells get activated by these stress hormones, and they send out inflammatory cytokines to deal with that potential threat. It’s an ancient and well calibrated system of communication between the brain and body to keep the organism safe. Whether it’s social threat, a biotoxin, or a predator, the response is the same: this is a matter of survival, so do your digestion, ovulation, or sleep later—now is not the time!

Most of you have heard that if you are chronically stressed, this has a negative impact on the body. But why is that? One of my favorite researchers on stress is a genius guy (literally he was awarded a Macarthur Fellowship) named Robert Sapolsky. Sapolsky is a biologist, professor of neurosurgery and primatologist from Stanford University. You Tube makes accessible his lectures on everything from human evolution, to depression, to why zebras don’t get ulcers (the title of one of his many books). They are hilarious, inspiring, and hugely educational.

Robert Sapolsky in 2023

Sapolsky is such an intriguing guy, not in the least because he recently dove off the deep-end of stress science and into a seemingly impossible marriage of neuroscience and philosophy. There are loads of entertaining videos of Sapolsky discussing his new book Determined: The Science of a Life Without Free Will, with his characteristic humor and energy.

In a video interview entitled “You Weren’t Designed to Live Like This” between podcaster Chris Williamson (of the trendy podcast Modern Wisdom) and Sapolsky, the professor discusses both the biology of stress and no free will. Sapolsky explains the evolution of the stress response (a safety mechanism of survival meant to be short-term) and how it becomes deadly when it turns into a chronic state of hyperarousal—which is exactly what PTSD is. This constant bathing of the body in stress hormones shuts down all kinds of systems that can only work when the body is in the parasympathetic (rest and digest mode), such as wound healing, repairing the brain during sleep, reproduction, digestion, and hormone regulation. Memory is significantly impaired, and the constant state of hypervigilance negatively impacts an area of the brain called the anterior singulate cortex, a part of the brain where you feel someone else’s pain. This means under chronic stress we are less empathic, less generous, and our range of concern narrows, biased towards our own self-interests.

Sapolsky points out that if a pregnant woman has an enlarged and overactive amygdala (remember, that’s the brain's fear-center), and especially if she is under any kind of stress, her fetus will be swimming in stress hormones throughout gestation, and itself will be born with an enlarged amygdala. Additionally, the fetus will be much more prone to developing PTSD, along with a host of other mental and physical illnesses.

I immediately think of my kids, who had the misfortune of being created by a body with an elephant-sized amygdala and a faucet of stress hormones that's frequently on full blast. Oh no! By the way, I've had two volumetric MRIs of my brain, both showing my amygdala in the 99th percentile. In contrast, the fearless free-solo rock climber Alex Honnold apparently has a miniscule amygdala. Makes sense, right?

Oh my god, you’re saying, is it all gloom and doom?! Well, not exactly…. the good news is there’s this thing called neuroplasticity, which means that the brain can remodel itself, neuropathways can change, and even brain structures like my ginormous amygdala can shrink in size over time… with a lot of intervention. And this is where I am right now, trying to figure out how to change my brain, one meditative moment at a time.

This brings me back to the book The Body Keeps the Score… the author claims that memory of trauma is encoded in our senses, in muscle tension, and in anxiety. So there for, healing must include the body; talk therapy, while helpful, is not enough. Besides Somatic Experiencing Therapy, much of what I’m doing are multiple practices throughout the day that involve vagal nerve stimulation, encouraging my nervous system to transition into the parasympathetic mode. For someone who has been addicted to adrenalin for a long time, and who has had anxiety since childhood, this is harder than it sounds!

Luckily for me, my flare-ups don’t seem to inhibit my creativity in the studio very much. In the first hours following a PTSD trigger, certainly I can’t relax enough to paint. But after a time, I find painting very therapeutic and relaxing. Painting keeps my mind connected to my hand, and it keeps me from dissociating, which was a coping strategy I learned as a little girl to survive the trauma I was experiencing. Walking in nature, and petting my dog are also very good for keeping me in my body and in the parasympathetic mode. I feel grateful that the universe gifted me a passion to paint. Painting gives my body the opportunity it needs to heal!

Thanks for reading this far and indulging the closet neuroscientist in me. I hope you learned something in this little essay! And thank you for your support. Please share with anyone who might appreciate it.

With love, 💗

Lise